Property & History

Few properties are as illustrative of Litchfield's connection to the colonial American architectural idyll and modernism, as Belden. A stay here connects you to both, and so much more.

A Singular Nexus

Boasting some of the most well-preserved colonial and colonial revival homes and estates in a village center, Litchfield itself is on the National Register of Historic Places for its representation of an eighteenth-century American town. But there is much more to Litchfield than its colonial architecture: Litchfield was a significant crossroad for and home to the first generation of American war heroes, those of the Revolutionary War. Litchfield was home to one of the country's first — and best — schools for women; home to the country's first law school, and then, in the twentieth century, was host to a modernist renaissance.

Litchfield

Founded by colonial settlers in 1715 in the northwest corner of Connecticut, what is now Litchfield County was the only area in Connecticut yet to be resettled by European colonists. We acknowledge that this land was stewarded by the Paugussett and Schaghticoke tribes, for thousands of years before European settlers made it their own. Originally called "Peantam" by the indigenous people (likely the root of settlers of European descent naming Bantam), Litchfield followed suit in the colonial tradition of renaming American places to emulate bustling British locales. Litchfield's purchase was negotiated between colonial representatives from Hartford and Windsor, CT, and some members of the Potatuck people, members of the Paugussett confederacy, the largest Algonquin nation in western Connecticut, and the deed for 45,000 acres was signed in nearby Woodbury, where the Potatucks retained an encampment on the Pomperaug River. The deed stipulated that the Potatucks retain land “sufficient for their hunting houses” near Mount Tom, creating the only known colonial-era Native American settlement in Litchfield.

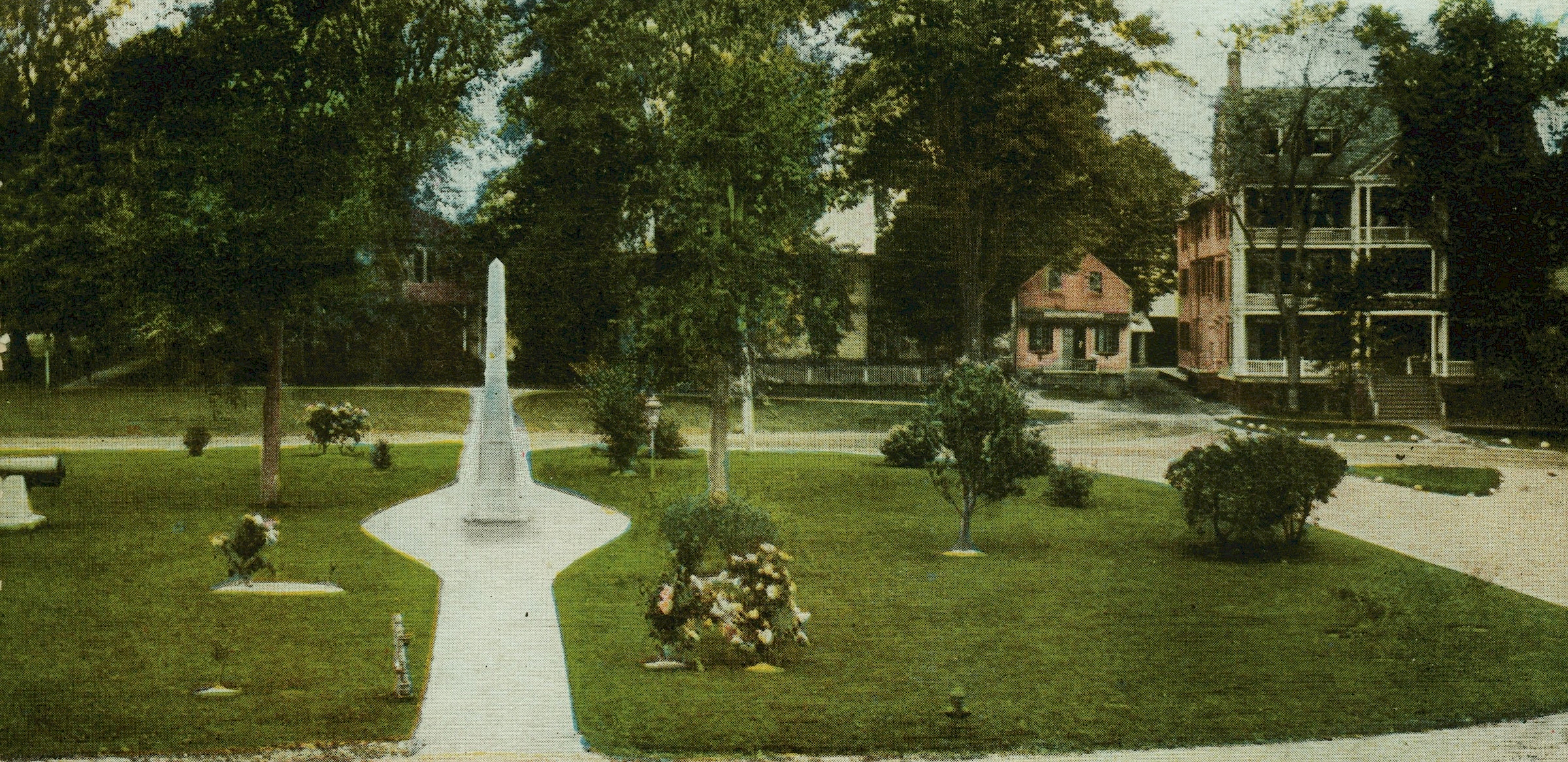

Pictured at top: The Litchfield Town Green photographed by N.D. Benedict, 1892. Courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society

Photographic Enlargement and Plan Stillman House: the second house (Stillman II) designed by Marcel Breuer for Mr. and Mrs. Rufus C. Stillman and located on Clark Road, Litchfield.Courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society

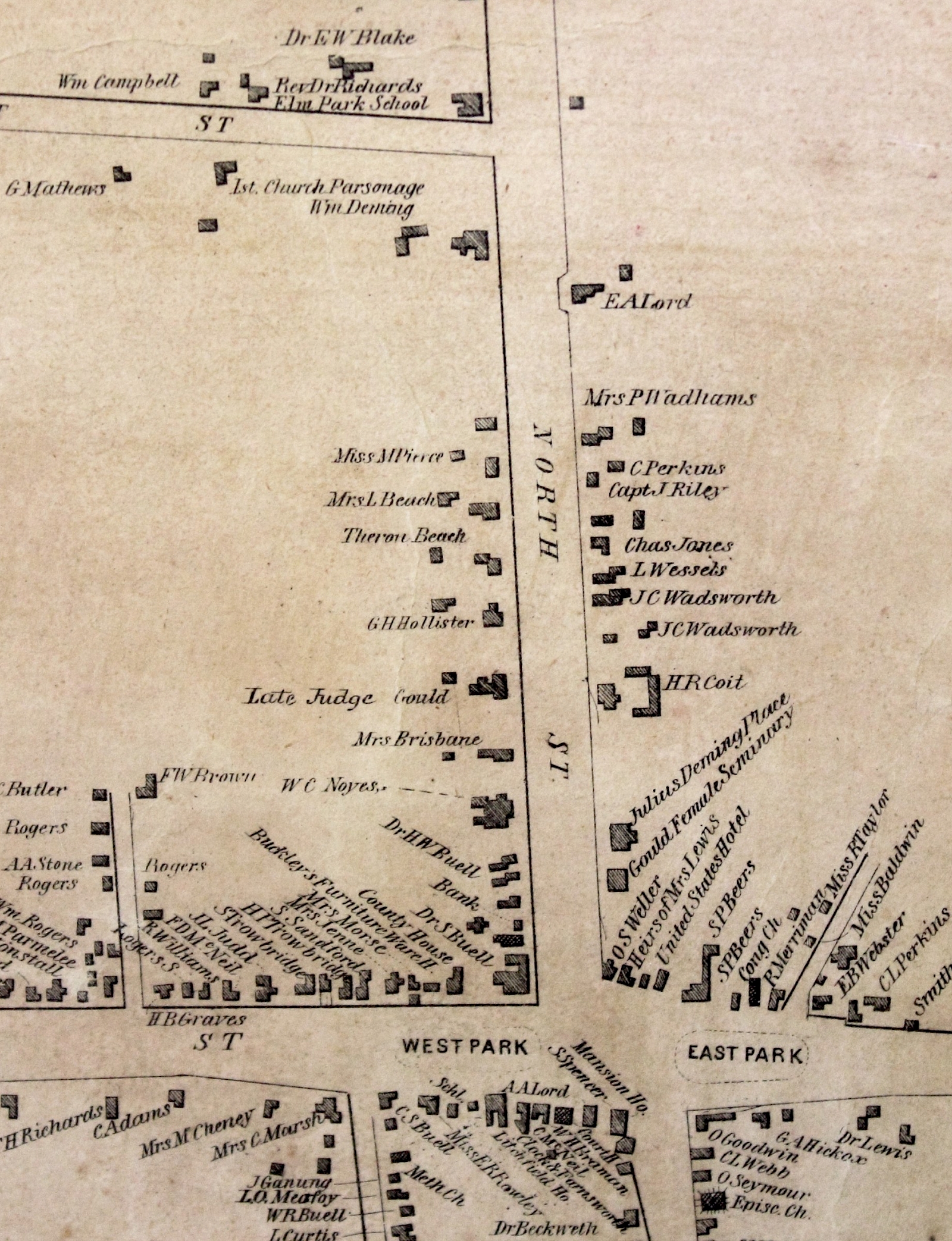

Map of Litchfield,1859, courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society

Photograph of Litchfield's First Congregational Church, courtesy of the First Congregational Church

Litchfield was founded under a sophisticated and forward-thinking proprietorship system, by which those involved were at essence becoming corporate partners. Early Litchfielders lived with the land, making linseed oil from flax and culling produce from fruit trees such as cherry, pear, apple, quince and apricot, all of which originated in England and were transported by early colonial settlers. Native New England grasses made for paltry hay, so the settlers introduced seed grasses like clover, alfalfa, sorrel and lettuces. There was no one who was not first a farmer, and produce, be it corn, tallow or pig fat, could be used in the place of money to pay taxes or debts.

In granting proprietors permission to establish a town, the colony’s General Assembly required that houses be “tenantable,” a term that then likely connoted sturdiness, but which resulted in homes that eventually often took in boarders, or tenants, in future generations. Town co-founder John Buell, who had settled once before in Lebanon, CT, and his cohorts brought with them the clever carpentry and aesthetic motivation that they had seen in already established Connecticut towns.

The town’s first meetinghouse (church) was completed by c. 1725, and then rebuilt in 1762, establishing an early precedent of civic improvement and rebuilding or renovating to meet the style of the day. Litchfield native and Uncle Tom’s Cabin author, Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896), whose father Lyman Beecher (1775-1863) was a Presbyterian minister at the church, described the second version as red with a white spire, a fanciful entry with a swan’s neck pediment, and a pulpit decorated with grapevines and red tulips; hardly austere imagery! The current meetinghouse of the First Congregational Church was built in 1829 and restored in its present location in 1929, in traditional proximity to the town green, which was always established as a “common” area (initially for grazing and as a very wide road), a part of the proprietorship that belonged to all stakeholders, emphasizing its central role for all Litchfielders. The First Congregational Church's story mirrors the town's centuries-long waltz with architectural nostalgia.

Putnam Phalanx on Litchfield Green c. 1920 by Adelaide Deming. Oil on canvas painting, genre scene, take directly from a photograph of Putnam Phalanx on August 2, 1920, State Day of the Litchfield Bi-Centennial, photo by W. N. Copley. Lines of marching men, in all, in blue uniform marhing across north Street, view of corner house and Phelps tavern. Courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society

The Revolutionary War & Litchfield

When the American War of Independence began, Litchfield quickly became a key munitions depot. The east-west artery through town connected “Boston and the Connecticut Valley with the colonial defense network at West Point, New York." General George Washington stayed in Litchfield at least twice over the course of the war and Litchfield County’s farms were an invaluable source of sustenance for the starving colonial troops. Oliver Wolcott, one of General Washington’s two recorded hosts on his visits, went on to be elected to the Continental Congress and was one of four representatives from Connecticut to sign the Declaration of Independence in 1776. The signing was only the beginning of the States' fight for freedom from Great Britain, and in April of that year, soldiers and members of the Sons of Liberty toppled a statue of King George III from its pedestal on Bowling Green in New York City. The dismembered statue was brought in pieces to Litchfield, where the Wolcott family and many members of the community convened in their orchard to melt it down. Principally, it was Litchfield women and children, led by the Wolcott women, who cast 42,088 cartridges from King George III’s likeness.

Benjamin Tallmadge, America's First Spy

Meanwhile, Major Benjamin Tallmadge, head of a dragoon unit, won the distinction of America’s first spy by finagling American agents behind British lines and securing intelligence on British moves in a secret operation called the Culper Spy Ring. After the war, Tallmadge moved to Litchfield's North Street and became a key member of the local political and business communities. Tallmadge and Oliver Wolcott, among others, became the first incarnation of American war heroes, which boosted their social standing and lent a whiff of American “aristocracy” to the town, attracting even more ambitious and industrious energy to its evermore bustling environs.

Photograph of the Tapping Reeve House in Litchfield, early 20th century. Courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society.

Tapping Reeve House: The Litchfield Law School

Tapping Reeve, who settled in Litchfield in 1772 and began taking students to tutor (including his brother-in-law, Aaron Burr, the future Vice President of the United States), was able to launch his law school in earnest after the war. The Litchfield Law School — “widely recognized as the first institution in America to teach common law with an organized, vocational curriculum preparing young men for the bar with a series of formal lectures” — was the cradle of American law. Tapping Reeve trained the individuals who went out and shaped the American legal system into what it is today. And he trained the individuals who went out and helped shape our county into what it is today. Amongst his students were two future vice presidents of the country, over one hundred future national Senators and Representatives, not to mention the countless state level senators, representatives, governors, judges, etc. that he educated. Given that his students came from different geographic regions, and from many backgrounds, Reeve brought together people of disparate ideals and political views and taught them how to have civil discourse with one another.

Pictured above: Portrait of Colonel Benjamin Tallmadge, an influential member of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, with his son William Tallmadge. This is a 1790 portrait by American painter Ralph Earl. Courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society. Pictured below: Oil on board study for a mural, 1949, portraying Sarah Pierce's Litchfield Female Academy by Nils Hogner (1893-1969). The full mural series was for Alexander Liggett's home on North Street home. Courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society.

Sarah Pierce's Female Academy

Likewise, women flocked to Sarah Pierce’s Female Academy (founded 1792), where she taught her students more than just ornamental arts, but how they too could become educators, one of the few professions available to women of this era. The new Connecticut turnpike system (1792) ferried over 3,000 pupils (120 of whom were boys) to Sarah Pierce’s school, and over 1,000 to Tapping Reeve’s law school. By 1798, Litchfield had established itself as an intellectual and business center, albeit surrounded by farmland, which was still central to the local economy. This generation's hands were not necessarily in the earth, though the earth here was highly profitable.

Home to William Grimes, the self-described "Runaway Slave"

Born into slavery in 1784 in King George, Virginia, William Grimes' life began the very same year that Connecticut enacted gradual emancipation legislation, "manumitting slaves born after March 1, once they reach the age of twenty-five." In 1787, when William Grimes was three years old and living on a plantation as an enslaved child, his white father, Benjamin Grimes Jr., owner of Eagle's Nest plantation, was having dinner with (then) General George Washington at Mount Vernon. The Constitution of the United States of America was being written and would be ratified in 1788. Washington would become the first President of the United States in 1799.

In 1815, after having had five "masters," William Grimes escaped slavery by hiding aboard the cargo ship Casket and sailing from Savannah, Georgia, to New York City. Grimes walked to New Haven, an early bastion of the underground railroad, where he worked a variety of jobs before eventually opening a barbershop in New Salem, MA. In 1818, after being twice accused and twice acquitted of assaulting a white woman, Grimes and his new wife, Clarissa Grimes* née Caesar, move to Litchfield, where he purchased land from celebrated Litchfield furniture maker Silias E. Cheney (the very same plot of land on which Firehouse now stands today). For context, in 1820, there were still ninety-seven African Americans held legally as slaves in Connecticut.

In 1824, Grimes unequivocally purchased his freedom from his last "master," who had traced him to Litchfield, for $500, an enormous sum for which Grimes had to mortgage his home. Just months later in 1825, Grimes published Life of William Grimes, The Runaway Slave, a harrowing first-person account of his life in slavery, in part to try to recover some of his finances. The Life of William Grimes is an early account of a formerly enslaved person in their own words, which, like the 1798 account by Venture Smith of East Haddam, CT, — fifty miles from Litchfield and another significant location in the Underground Railroad and Freedom Trail — paved the way for more well-known accounts, such as the three accounts by Frederick Douglass.

*In this lesser-known history lies a tie to Belden's sister property, Troutbeck: Clarissa Grimes' descendants — members of the Cesar family — were longtime employees of Joel and Amy Spingarn, the couple who bought Troutbeck in the early 1900s and who were early civil rights activists. In this extraordinary way, Troutbeck and Belden are already linked in history.

All quotations and information above are from the most recent edition, co-edited by Grimes' great-great-great granddaughter, Regina Mason, which we strongly recommend reading in full.

Mollie Belden, Mary Vought, Walter Hodgemale, Nan Vought, Mary Webster, Dr. Charles Belden, Courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society

Portrait of Belden children, Courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society

Belden House

The first residential building north of Litchfield's thriving commercial district, Belden House was built for Dr. Charles O. Belden in 1888, on property Belden purchased from Samuel Buell, a descendant of John Buell (1671-1746), who co-founded Litchfield in 1718. With its fanciful spires, hip roof followed by conical gabled pavilions, demilune windows, and Doric pilasters, Belden House is illustrative of the Victorian and Queen Anne styles that were at play, alongside colonial revival architectural style, prevalent here near the end of the 19th century. Within, Victorian elements, such as the ornately and somewhat humorously carved mantels, stained glass windowpanes, detailed wall paneling, parquet floors and window seats proliferate.

"Colonial revivalism" was about more than architecture. Litchfield became a summer “colony,” where captains of industry flocked to relax and, frankly, to show off — though Litchfield's version was notably less showy than that of Newport, Rhode Island, another New England summer colony of this era. In Litchfield, colonial revivalism was more than just a style, it was a way of life. Prominent families held colonial teas and balls and replaced or remodeled elaborately ornamented Victorian homes with white-columned 18th century-style houses along North and South Streets in an exaggerated effort to evoke images of the town’s past.

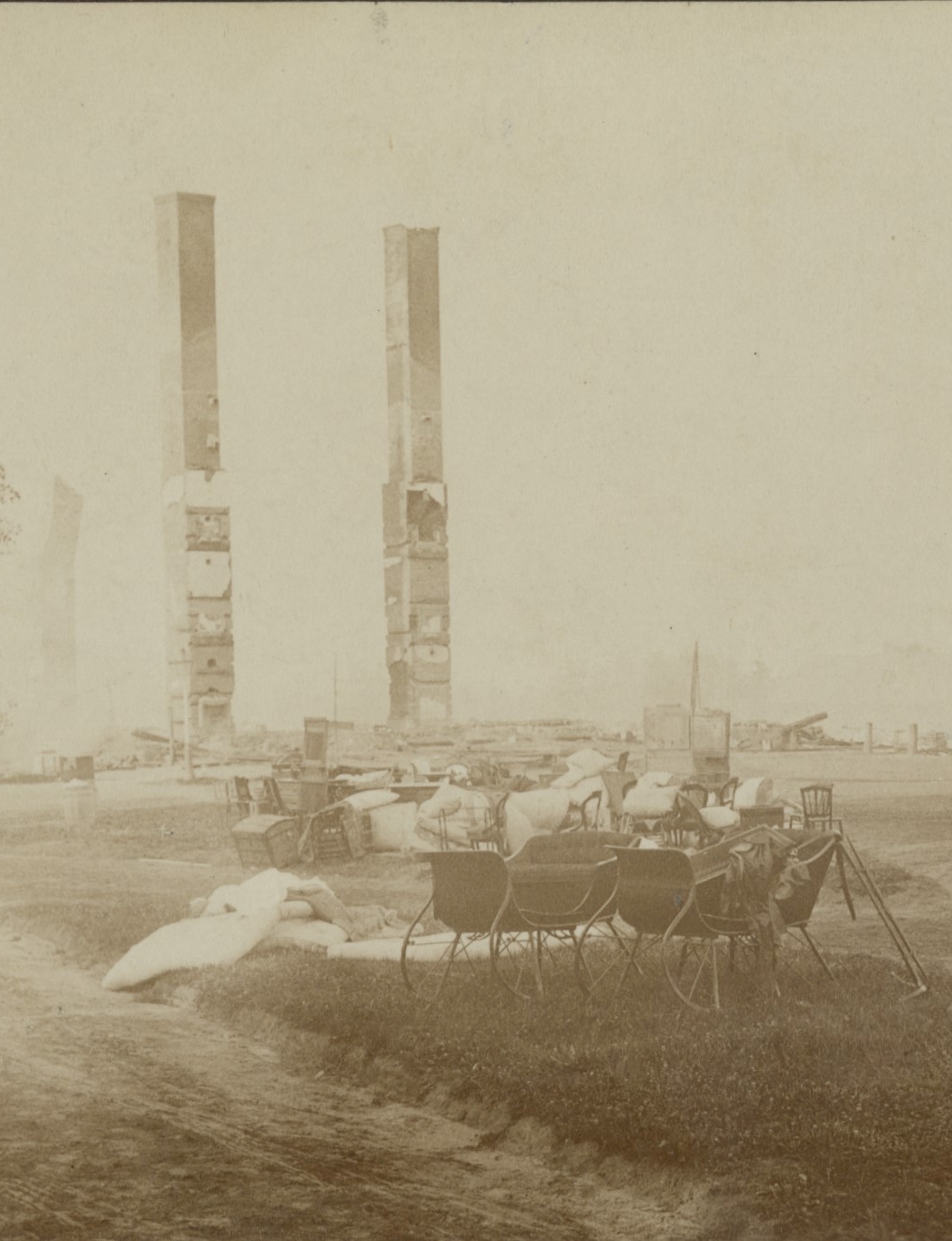

View of Litchfield green after 1886 fire, N.D. Benedict, courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society

Postcard featuring the Litchfield Firehouse, Karl Brothers, courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society

Firehouse

Disastrous back-to-back fires in 1886 and 1888 left the town center — including the Mansion House Hotel (built c. 1800) — destroyed and inspired the formation of Litchfield’s first public water system and the Litchfield Fire Company, headquartered in our landmarked brick building on West Street right on the green. The "new" firehouse was underwritten entirely by Julius Deming Perkins, a Litchfield devotee who summered here at the height of the town's "summer colony" status. He enlisted noted Waterbury architect Robert Wakeman Hill, who was architect for the state from 1881 to 1889, to create an unshakable fire fighter's fortress, that included a community center with a bowling alley, billiards room, reading room and hospital facilities.

Coupled with the imposing Romanesque granite courthouse (also by Hill) across the green, these two edifices sent a strong visual message about Litchfield's tenure: the town was doubling down on civic betterment. Deming Perkins, who was an active member of the Village Improvement Society, was also responsible for creating Litchfield's first public water system, "watering" the roads, to keep the dust from horsedrawn vehicles down, and lighting the streets at night.

"The only street in America more beautiful than North Street in Litchfield is South Street in Litchfield."

Sinclair Lewis, Nobel Prize-winning author & playwright

The Village Improvement Society notably took an early interest in preserving Litchfield's history and protecting its architectural heritage, placing plaques on edifices that bore an 18th century date. The roots of the Litchfield Historical Society began in 1856, but in the 1890s it was reenergized thanks to Emily Noyes Vanderpoel (1843-1939), the great-granddaughter of Benjamin Tallmadge, who acted as its first curator and passionately collected for its repository for forty years.

In 1913, the Village Improvement Society hired John C. Olmsted of Olmsted Brothers, founded by Frederick Law Olmsted, to advise on a proposed revamping of the village green. Olmsted never drew up plans for the green and his advice for its renovation was not followed, but he did suggest state laws to limit building height, restrict commercial construction in residential areas, and impose rules for architectural styles, a prescient notion far ahead of its time in terms of zoning.

In 1929, the Litchfield Historical Society pledged more than $200k to restore the Tapping Reeve House (82 South Street) and Law School property, following period examples in comparable structures, rather than based on evidence of what it would have looked like when it was built in c. 1773, proving that Litchfield's Colonial Revival mentality persisted well into the 20th Century. Just as Tapping Reeve House and the Congregational Church restoration were taking place, the town lost its last major hotel, when the Phelps Tavern was demolished due to disrepair. Until 2024, Litchfield has not had a high street hotel in the nearly 100 years since. Nearly in tandem with the destruction of Phelps Tavern, the last of Litchfield's old guard original hotels, in 1938, Litchfield took its first substantive preservation measure: a local ordinance prohibiting new construction and alterations to any existing property in the Litchfield Borough chartered in 1885 without approval from its Board of Burgesses — this ordinance was the first of its kind for a Connecticut town.

Rufus and Leslie Stillman House, built 1950 by architect Marcel Breuer with mural by Alexander Calder

Photograph by Kmsena - took photo, CC BY-SA 3.0, wikipedia.com

"If MoMA thought he was that good, then we shouldn't argue about it."

Rufus Stillman on Marcel Breuer's architectural designs

Modernism in Litchfield, Hiding in Plain Sight

As the world found its footing after the Second World War, artists and designers — ever the bellwethers of civilization as a whole — began creating a new visual lexicon to represent a completely modern moment. Hungarian-born Marcel Breuer left his post at Harvard's Graduate School of Design and partnership in modernist godfather Walter Gropius' Boston firm to strike out on his own in New Canaan, CT. It was there that new Litchfield resident, Rufus Stillman (a nephew of Topsmead doyenne Edith Chase) and his wife Leslie, found and commissioned their new home by Breuer, one of three homes that the architect would eventually complete for the Stillmans in Litchfield. Stillman I (1950) featured original and highly functional interior designs for the modern family, as well as an interior mobile and a poolside mural by Breuer's friend, Alexander Calder.

The appeal of bucolic Litchfield and the forward-thinking Stillman House I were contagious, and soon the Stillman's friends, Dr. C.H. and Mary Huvelle were hoping to grow roots in the burgeoning modernist community. The Stillmans were happy to sell them half of their plot so that they could be neighbors, on the condition that they built themselves a thoroughly modern home. Breuer protégé, John Johanson, was hired, and with the Huvelle House (1950), a modernist enclave was established on a cul de sac, set back from the Litchfield colonial facades long associated with the American architectural idyll. Meanwhile, in nearby Milton, Stillman's sister Kathy and her husband Ted Marsters were collaborating with architect Edward Larrabee Barnes on their own stone and glass modernist home.

By 1953, Breuer was a household name in Litchfield and had signed on for three public commissions: two elementary schools in Bantam and Northfield, and the Litchfield junior high school. The Connecticut community had fully bought into the au courant notion that exposure to architecture, art and aesthetically inspiring environs could themselves bolster creative thinking, "vocational and homemaking skills." Breuer's junior high school allowed a view of outside from virtually every space, but its most stunning achievement was its glass-walled, fish-shaped gymnasium, inspired by a design his mentor Walter Gropius had shown in an exhibit years before.

Oliver Wolcott Library "OWL" photographed by Cedric Gairard

Perhaps no building better encapsulates Litchfield's connection to design revelations in a variety of historical moments than the Oliver Wolcott Library, known fondly as OWL, at 160 South Street. Litchfield's public library was first established in 1862, as the Litchfield Library Association, and eventually was housed in the Beaux Arts brick building that is home to the Litchfield Historical Society’s Litchfield History Museum and Helga J. Ingraham Library. To contend with a need for more space, in 1966, the town moved the library to the former home of Oliver Wolcott Jr., the second United States Secretary of the Treasury, a judge of the United States Circuit Court for the Second Circuit, and the 24th Governor of Connecticut. Modernist architect, Eliot Noyes, a New Canaan resident and — with Breuer, Johansen, Landis Gore and Philip Johnson, the five modernist architects who settled there known as the Harvard Five — was employed to erect an expansive additional wing. At OWL, Litchfield's singular history of colonial nostalgia and modernist invention combine as a public home to books, the diaries of history.

Now with Belden House & Mews, another Litchfield property unites these two significant architectural moments, and — with painstaking respect for their original details — roots them in the present, so that the contemporary traveler may experience the varied natural and cultural offerings of this fascinating Connecticut town.

The history outlined here and many images of Litchfield and art produced by its residents throughout the Belden site are thanks entirely to our community partners at the Litchfield Historical Society, who have been incalculably generous with their knowledge, archive and time.

Litchfield: The Making of a New England Town by Rachel Carley has been instrumental in our research, and we recommend you pick up a copy when you visit the Museum. All items in the body of text that are in quotations here are taken from this outstanding text that studies the history of the town through the architecture its residents erected.

William Grimes, Runaway Slave is a revelatory work and is available in its most recent edition, co-edited by his great-great-great granddaughter Regina Mason and William L. Andrews